Ido Kisaemon x Tea leaf jar with design of wisteria: the simple and the elegant of chanoyu

Overview

Featuring two chanoyu-related national treasures

Chanoyu is a quintessential cultural practice of Japan, which developed over nearly a millennium to form a composite art. Originally, Chinese ceremonial tea service was introduced to Japan in the 12th century, together with ceramics related to the practice. In the Muromachi period (14th-16th centuries), such imported tea utensils were cherished by nobles and ruling-class samurais, notably the Ashikaga clan. The possession of rare items thus became a symbol of power. Toward the end of the 15th century, a new style of tea known as wabi-cha was created by Murata Jukō (ca. 1423–1502), to appreciate simplicity in a purposefully choreographed setting, sōan (a frugal little hut). Takeno Jōō (1502–1555), a wealthy merchant in the Sakai district of Osaka, promoted this particular style of tea among urban commoners. Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) subsequently established a formalized method of chanoyu. Various practitioners further developed the art, introducing their own aesthetic sensitivities into the practice and, in this way, extending the scope of artistic relevance to other domains, such as calligraphy and architecture.

Under the theme of “wabi” (rustic simplicity) and “miyabi” (refined elegance) as quintessential features of Japanese culture, the Exhibition invites visitors to marvel National Treasures Ido Kisaemon (Kohō-an) and Tea-leaf Jar with a design of Wisteria (MOA Museum of Art) together, for the first time in 36 years. Select articles of tea utensils from the MOA Museum of Art collection complement the curation, showcasing the beauty and charm of Japan’s unique practicing art, chanoyu.

Galleries

Kisaemon, ōido type tea bowl, National Treasure Joseon dynasty, 16th century, Kohō-an collection

The culture of chanoyu flourished in the 16th century. This was a period when tea bowls from the Korean peninsula were highly sought after. Among them, the ōido type was considered to be of the highest value, and prominent samurais and tea masters were eager to have their hands on one. The national treasure Ido Kisaemon is so called after its original owner Takeda Kisaemon, a merchant of Osaka. It has always been acclaimed to be the Ido type par excellence. The bowl was subsequently acquired by Matsudaira Fumai in the latter part of the Edo period. After his death, it was donated to the Kohō-an of Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto.

Tea-leaf Jar with design of Wisteria, National Treasure by Nonomura Ninsei, Edo period, 17th century

Nonomura Ninsei established his own kiln in around 1647 near Ninnaji Temple in Kyoto. His work was characterized by the aesthetics of elegant Imperial culture, embellished with gold, silver, and rich colors. This jar used to be in the possession of the Kyōgoku clan for generations. Its creation date is estimated to be around 1673 according to the clan’s family inventory. The wisteria design is arranged so that the racemes hanging from the vines are distributed in such a way as to form a seamless composition around the vessel. The racemes are rendered in red, silver, and violet pigments while the leaves are detailed with capillaries. This article is acclaimed to be Ninsei’s magnum opus.

The ultimate “wabi” style tea bowl, embodying Rikyū’s aesthetic preferences

AYAME, Kuro-raku type tea bowl, Chōjirō, Momoyama period, 16th century

A nest of tea bowls with a striking design

Pair of Tea Bowls with Lozenge Design in Gold and Silver, Important Cultural Property, Nonomura Ninsei,

Edo Period, 17th century

The Muromachi period saw a rising popularity of collectable Chinese ceramics (referred to as karamono), which ruling class samurais liked displaying in their residences and using them for ceremonial tea-drinking. The shogunate clan of Ashikaga had an inventory of the family collection of karamonos, evaluated and categorized by a gild of artist-Buddhists. This was used as a basis for the room decoration guidelines established subsequently. The Ashikaga collection is a rich archive of the karamono enthusiasm, and the Higashiyama miscellany, a part of the collection including chanoyu utensils, is featured alongside related tea utensils.

The karamono tea caddy of the class omeibutsu, or “the most precious articles”

Karamono tea caddy of the Hamuro Bunrin type, Southern Song China, 12th–13th century

Liang Kai’s masterpiece affixed with the surveyor seal of Ashikaga Yoshinori,

the sixth shogun of the Muromachi shogunate.

Hanshan and Shide, attributed to Liang Kai, Southern Song China, 13th century

Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) took control of Sakai, a town in Osaka where the enthusiam of chanoyu was most pronounced. The warlord confiscated valuable chanoyu utensils from townspeople, and the spoils of this campaign were used for his political maneuver. He engaged three most prominent tea masters of Sakai as his official advisors of tea affairs, namely Imai Sōkyū (1520–1593), Tsuda Sōgyū (birth unknown–1591), and Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591). Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), who came to rule Japan following Oda’s downfall, retained these tea gurus and threw lavish tea ceremonies in Kyoto, resulting in proliferating chanoyu into popular culture. The exhibits also include masterpieces owned by other sixteenth-century warlords such as Tokugawa Ieyasu and Date Masamune.

The tenmoku type tea bowl with its rustic charm, once owned by Date Masamune

AKIHA, haikatsugi-tenmoku type tea bowl, Southern Song to Yuan China,

13th-14th century

The scroll once belonged to Oda Nobunaga

Myna Bird, attributed to Muqi,

Southern Song China, 13th century

Furuta Oribe was an accomplished tea practitioner as much as he was a military commander. Some believe that he apprenticed chanoyu under Sen no Rikyū and came to prominence after the death of the tea master. His preference of style veered toward wild and powerful, agreeable to his warrior standing, reflected in the dynamic designs of Iga ware vessels as well as subtly deformed tea bowls known as “hyogemono.” Kobori Enshū is believed to be trained by Furuta Oribe. The Tokugawa shogunate engaged him as the shogun’s official instructor of tea. His taste in chanoyu was lavish and colorful: he gave instructions on designs of Takatori and other domestic ware tea caddies and directly commissioned Chinese kilns to produce classical blue-and-white as well as Shonzui (Xiang-rui) ware ceramics. His adoration of the aristocratic culture of the bygone Heian period was manifest in his naming utensils after famous classic poems, and his style that favored refinement became known as kirei sabi, or “the elegant sabi style.”

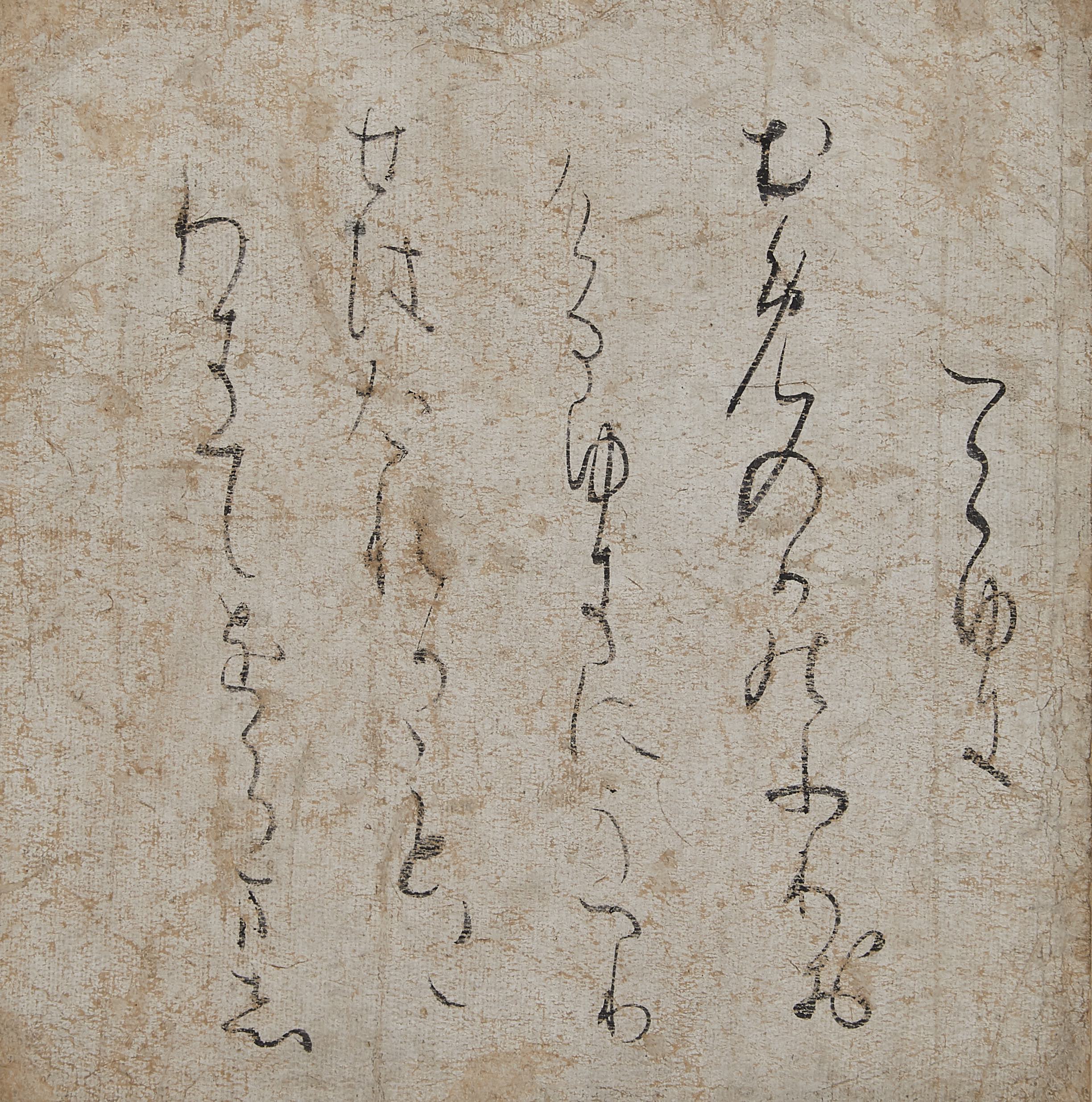

A fragment of classical calligraphic work (“kohitsu gire”) which Enshū favored to display in the background of chanoyu practice

Sunshōan poem paper, Heian period,

late 11th century

A vessel exhibiting the characteristics of bold Iga ware: animated shape, natural glaze, and scorching marks

Iga ware double-lugged vase,

Momoyama period, early 17th century