HOMO FABER, 12 Stone Garden Naoto Fukasawa and 12 Living National Treasures

Earlier in spring this year, the Michelangelo Foundation organized an exhibition, Homo Faber Event, between April 10 and May 1 in the Italian city of Venice as part of the city’s international art exhibition, Biennale Arte 2022. The 12 Stone Garden was presented as part of its programs to showcase the work of twelve Japanese Living National Treasures (individuals designated as preservers of significant intangible cultural heritage), displayed in a space arranged by designer Naoto Fukasawa. The exhibits mesmerized art fans from across the world, stirring enthusiastic responses to the world of Japan’s finest handicrafts. The exhibition Homo Faber 12 Stone Garden: Naoto Fukasawa and 12 Living National Treasures has resulted from an earnest desire to recreate its overwhelming success back in Japan and is curated by Fukasawa himself and the Museum’s director Uchida Tokugo. Masterpieces of the twelve participating craftspersons fill this specially designed space together with images created by photographer Rinko Kawauchi. Come and experience the wonder of Japanese kōgei art and craftsmanship at MOA Museum of Art this autumn.

Robilant ©Michelangelo Foundation

Laila Pozzo ©Michelangelo Foundation

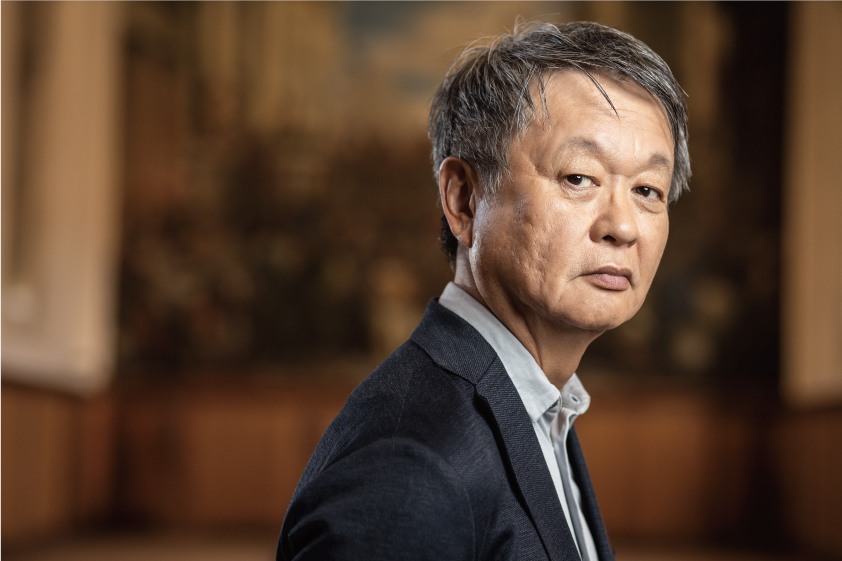

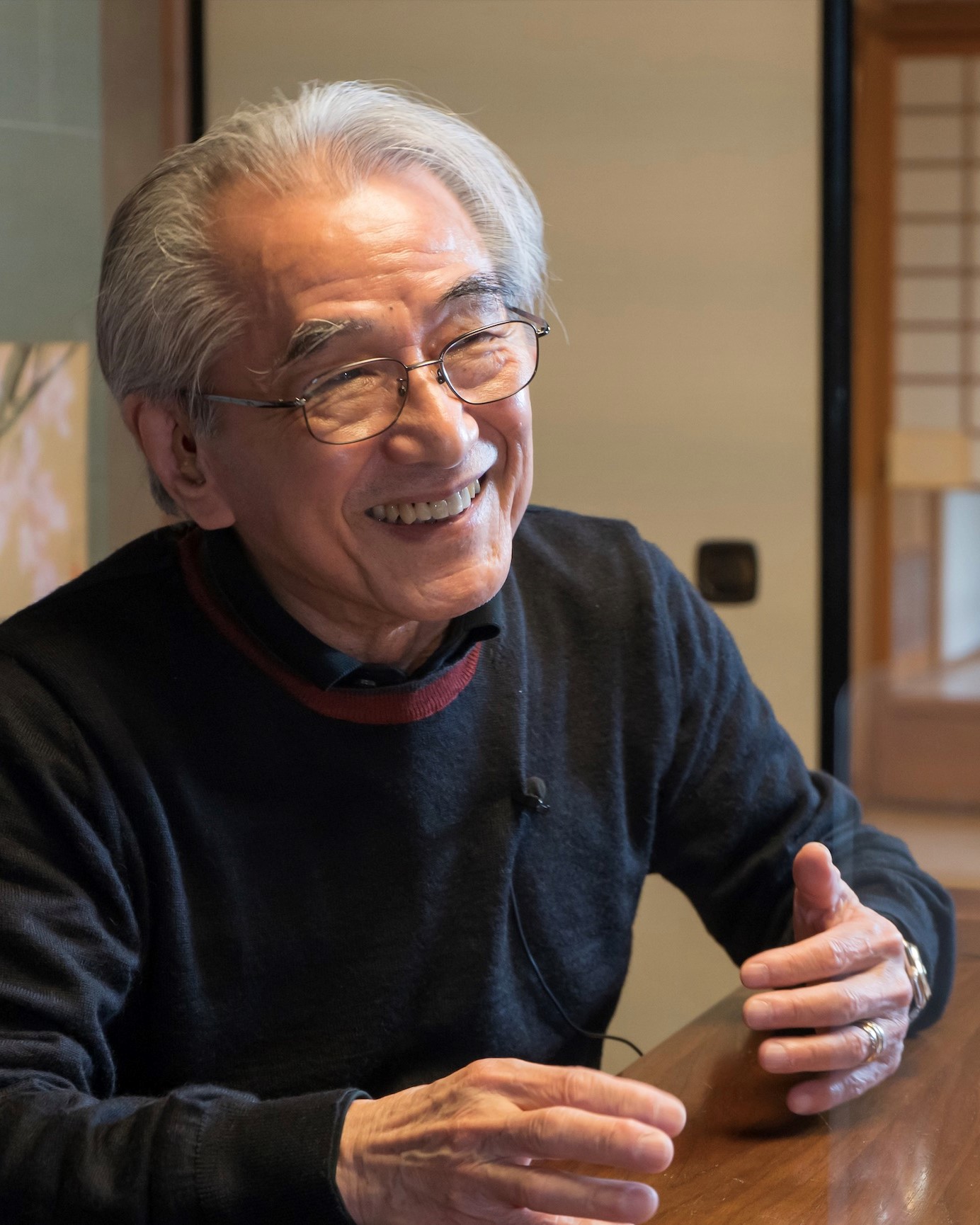

深澤直人 | FUKASAWA Naoto

Born in Yamanashi Prefecture in 1956. Graduated from Tama Art University’s Product Design Department in 1980. Fukasawa honed his career in design for seven years, focusing mainly on Silicon Valley industries before returning to Japan in 1996. He established and headed IDEO’s Tokyo office, creating a Japanese design consultant base for the company. He went independent in 2003 and founded NAOTO FUKASAWA DESIGN. Currently, Fukasawa designs for a wide range of leading brands worldwide, as well as consulting and designing for local Japanese companies. Fukasawa is the curator of The Japan Folk Crafts Museum. He is a professor in the Integrated Design Department at Tama Art University and one of the directors of 21_21 Design Sight. He also sits on the design advisory board of Muji. He was awarded the Isamu Noguchi Award in 2018.

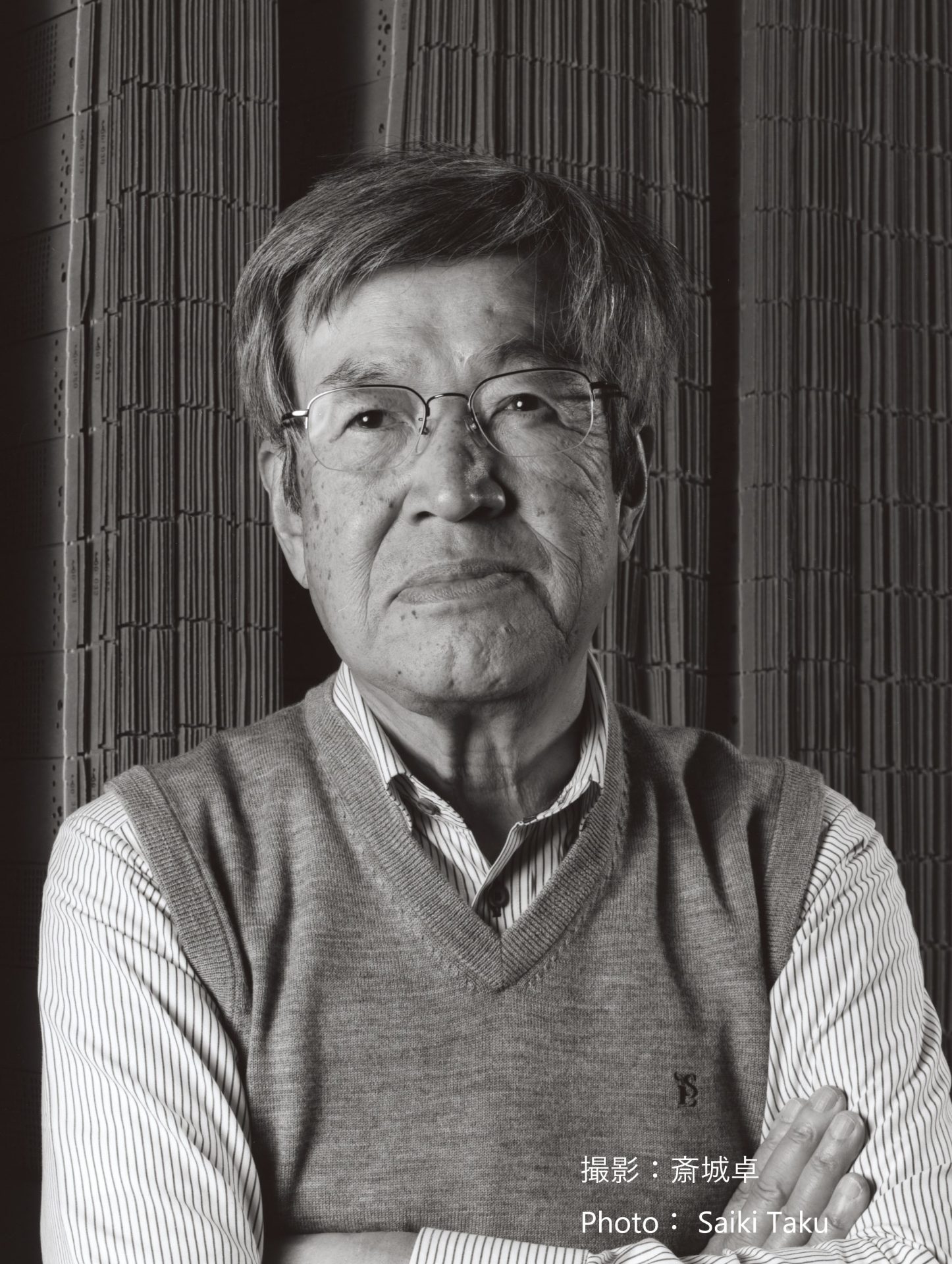

内田篤呉 | UCHIDA Tokugo

Born in Tokyo in 1952, Uchida is a graduate of Keio University, with a doctorate in Aesthetics. He specializes in Japanese art history. He is currently the executive director of MOA Museum of Art and Hakone Museum of Art. Prior to this appointment he held a range of academic positions including visiting professor at Kyushu University, part-time instructor at Ochanomizu University Graduate School, Keio University, Tokyo University of the Arts, Musashino Art University and Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts. He has also been a member of the Council for Cultural Affairs of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and also a member of the World Cultural Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage committees. Among his publications are Urushimono Chaki no Kenkyu (Study of Lacquerware Tea Ceremony Utensils) and Suzuribako no Bi ‒ Maki-e no Seika (Beauty of Inkstone Cases: the Essence of Maki-e), both published by Tankosha Publishing, and Korin Maki-e no Kenkyu (Study of Maki-e by Korin) published by Chuokoron Bijutsu Shuppan. He edited Korin ART ‒ Korin to Gendai Bijutsu (Korin ART ‒ Korin and Modern Art) published by Kadokawa Gakugei Shuppan Publishing.

The Person, Technique and Work of the Artists―12 Living National Treasures

伊勢﨑淳 | ISEZAKI Jun

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of Bizen ware pottery, designated in 2004

Jun Isezaki, born in 1936 in Bizen city, finished his university education in Okayama and apprenticed under his father to develop skills and techniques in pottery. His first award in 1961 was followed by the Kaneshige Toyo Prize and Tanabe Museum of Art award. Later, he embarked on a travel in Europe and America, during which he made acquaintance with Joan Miro and Isamu Noguchi, two influential figures who inspired Isezaki to master artistic pottery.

Techniques and Works

Bizen ware pottery is characterized by a firing technique without any pre-applied glaze, and a highly malleable iron-rich clay known as “tatsuchi.” Isezaki uses iron-rich brown clay and practices slow firing, which takes more than ten days to complete. He does not apply glazes to his work. Instead, decorative effects come from the kiln during firing, such as fine dots created by ashes of the burning logs and madder red strips achieved by wrapping the pottery in straw.

Angular Vase was created for Homo Faber Event 2022 in Venice. While perpetuating the century-old Bizen ware tradition, Isezaki believes that “tradition stems from exploration into new frontiers and, rather than through understanding, it is, or should be, communicated through creativity.”

Angular Vase 2020Jun ISEZAKI

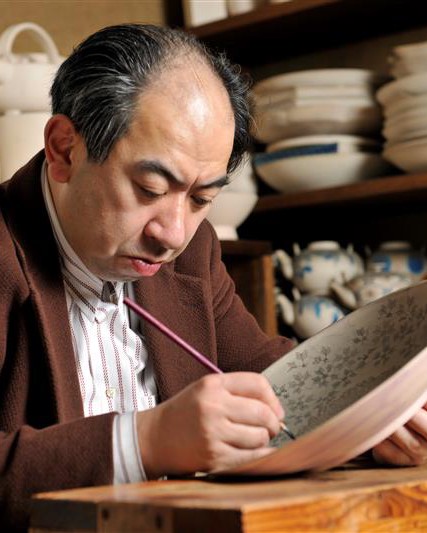

十四代今泉今右衛門 | IMAIZUMI Imaemon

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of overglazed porcelain, designated in 2014

Imaemon Imaizumi was born in 1962 in Saga. The family was employed by the Nabeshima clan in the seventeenth century as an official overglaze artisan for Nabeshima ware. Imaemon studied industrial and craft design at Musashino Art University, then apprenticed in artistic pottery under Osamu Suzuki, a renowned pottery artist.

Techniques and Works

Nabeshima ware originated in the seventeenth century, created for the purpose of gift-giving to the Tokugawa shogunate. The process involves firing underglazed pottery, onto which designs are overglazed before firing it again at lower temperatures. Imaemon innovates by creating new expressions of Nabeshima pottery through combinations of techniques, such as sumi-hajiki, and by introducing new materials such as platinum foil. Sumi-hajiki is a stencil-like ink-based glazing technique—a design drawn in ink resists the glazes which are applied subsequently and burns away during the firing.

The bowl with a passionflower design is based on an arrangement of traditional snowflake patterns. Imaizumi XIV believes in perfecting processes that are discrete but essential to enhance the end result.

Bowl with passionflower design in overglaze enamel and sumi-hajiki (reverse-pattern stenciling) 2007Imaemon IMAIZUMI

福島善三 | FUKUSHIMA Zenzō

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of Koishiwara ware pottery, designated in 2017

Zenzō Fukushima was born in 1959 in Koishiwara, Fukuoka. Zenzō went to Fukuoka University for higher education, but after graduation, he returned to his father and grandfather to learn Koishiwara ware pottery.

Techniques and Works

Koishiwara ware was originally established in the village of Toho in Fukuoka toward the end of the seventeenth century, developed from Korean pottery-making techniques. The raw materials of Koishiwara pottery is locally sourced iron-rich clay, and its mainstream products include everyday utensils such as plates, bowls, urns, pots and mortars. Fukushima has created a deep celadon blue achieved through reduction firing, the color he calls Nakano Geppaku.

An excellent amalgamation of Koishiwara celadon blue and Fukushima’s creativity can bee seen in his Nakano bowl with a moon-white celadon glaze 2013. Besides the celadon blue, an iron color, a rusty red hue and many other effects are achieved through oxidation firing and an array of glazes, broadening the range of his Koishiwara pottery. He holds a creative principle of using the raw materials from his hometown and making something new, to help the tradition survive and move forward.

Nakano deep bowl with a moon-white celadon glaze 2013Zenzō FUKUSHIMA

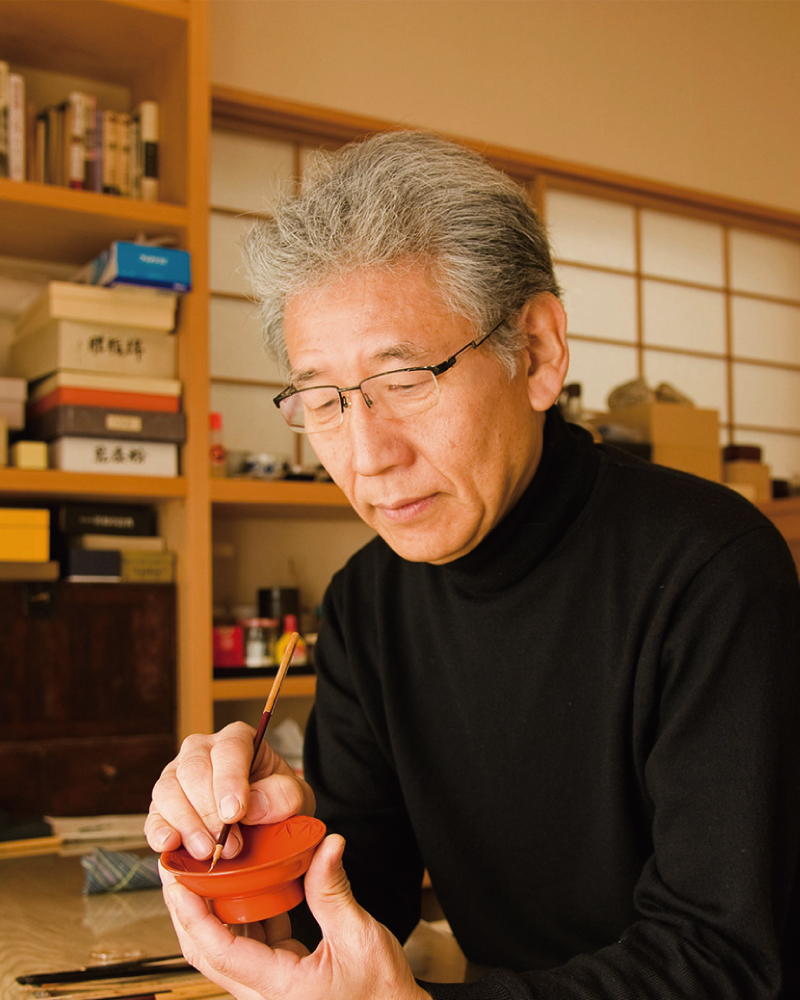

室瀬和美 | MUROSE Kazumi

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of maki-e, designated in 2008

Kazumi Murose was born in 1950 in Tokyo. He studied lacquer art at Tokyo University of the Arts. Gonroku Matsuda (a Living National Treasure) was another mentor, from whom he learned an approach to creative activities based on observing and deepening his understanding of people, objects and nature. He is an active contributor to the Japan Traditional Art Exhibition. His excellent skills in lacquer art partly owes to his experience in restoring, preserving and copying historically valuable works of art. The experience has also enriched his authentic understanding of Japanese aesthetic expressions, based on which he creates lacquerware that amalgamates Japanese traditional methods enhanced by modern perspectives with elegance.

Techniques and Works

Maki-e is a design technique for lacquerware. It involves drawing designs with urushi and sprinkling fine metal powder onto them. Murose had the opportunity to join a scientific investigation of the sward that represented the roots of maki-e in Japan, an eighth-century treasure housed in the Shōsō-in in Nara. On this occasion, he recognized that each grain of gold dust contributed to the overall expression of the maki-e design. He says, “Maki-e followed a technique-driven development through the medieval period to pre-modern times, which led to extremely technical works in the nineteenth century.

The harp Seiyu (Journey to the West) is an Italian Salvi harp to which Murose applied maki-e with mother-of-pearl inlay to express the cultural connections between West and East, represented by the vine arabesque.

Harp with maki-e and inlay decoration “Journey to the West” (detail)

Harp with maki-e and inlay decoration “Journey to the West” 2007Kazumi MUROSE

大西勲 | ŌNISHI Isao

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of kyūshitsu, designated in 2002

Ōnishi, born in 1944 in Fukuoka, took apprenticeship under Yūsai Akaji (a Living National Treasure) to master kyūshitsu lacquer application techniques.

Techniques and Works

Ōnishi undertakes the entire process of creation himself, from the selection and preparation of raw materials to the application of urushi and the finishing polish. Ōnishi’s work typically involves the magewa-zukuri technique—bending strips of wood to form the base structure. He also makes his own urushi lacquers using select fine materials.

The Food Vessel in magewa (bentwood work) 2011 showcases the finest of kyūshitsu-style artistic lacquerware. “The beauty of urushi is enhanced by perfecting each coat, executing the application and polishing the surface meticulously,” says Ōnishi. His work is a result of his dedication to each process, for which it is highly appreciated. There is no compromise in his work processes, from the base-forming to the finishing polish, executed singlehandedly.

Food Vessel in magewa (bentwood work) 2011Isao ŌNISHIGerald Le Van-Chau ⒸMichelangelo Foundation

林駒夫 | HAYASHI Komao

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of tōso dolls, designated in 2002

Komao Hayashi was born in 1936 in Kyoto. He learned doll-making from Shōzō Okamoto, a master creator of imperial dolls. He then apprenticed under Nyoi Kitazawa to master Noh-mask making and learned Yūzen-style textile dyeing at the atelier run by his maternal relatives. His work thus reflects the local history and the classical performing arts of Kyoto.

Techniques and Works

Tōso, the main material of the dolls, is a mixture of wood flour and glue, which is highly elastic, adhesive and moldable. Once dry, the tōso hardens and can be carved like wood, making the material ideal for achieving a subtle complexion and highly aesthetic composition. Hayashi is adept at working with tōso to express subtle emotions. Elegance is his approach to the selection of materials and execution of skills, yet he says “it is not the techniques but the perceptive mind that completes a doll. This is the principle underlying my work.”

Lady enjoying the moon-viewing party in the court represents a court lady gazing at the moon. Hayashi strives to “express what essentially has no visual representations.” Thus, this doll expresses the moonlight. For Hayashi, dolls are representations of sacred beings, and his figures embody the spiritual profundity in human forms.

Japanese doll formed with tōso over wooden core and covered with paper “Lady enjoying the moon-viewing party in the court” 2017Komao HAYASHI

藤沼昇 | FUJINUMA Noboru

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of bamboowork, designated in 2012

Noboru Fujinuma, born in Tochigi in 1945, started his apprenticeship under the bamboowork artist Keizō Yagisawa in 1976 to acquire traditional techniques, which he pursued further and out of which he developed various expressions. He traveled to France as a young man, and on his return to Japan, Fujinuma began searching for ways to promote Japanese culture. A turning point came as he discovered the mesmerizing work of Shōunsai Shōno, which motivated him to master the art.

Techniques and Works

Japanese bamboowork is broadly divided into two categories: one based on weaving techniques and the other that uses a piece or fragment of bamboo. In both cases, the material offers simple beauty and flexible and durable properties. Fujinuma’s work often combines several weaving techniques and creates unique forms, leveraging the material's natural properties.

Spring Tide expresses the kinetic energy permeating the famous whirlpools of Naruto channel in Tokushima. The thematic idea underlying Fujinuma’s work is chi, or energy. “The intricacy and sturdiness of bamboo derive from the chi of the plant,” says Fujinuma. “And when this chi meets my personal energy, the resulting work has a message to convey.” True to his words, his works have the sense of energetic expansion and all-embracing forms.

Bamboo flower basket “Spring Tide” 2017Noboru FUJINUMA

須田賢司 | SUDA Kenji

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of woodwork, designated in 2014

Kenji Suda was born in 1954 in Tokyo. Having acquired skills in traditional joinery from his father Sōsui, Kenji pursued his own exploration to enhance his woodworking techniques and ways of expressions.

Techniques and Works

Japanese joinery is called sashimono which signifies “work with precision.” Suda often employs a technique called kumite to join two pieces of wood together to make wooden boxes. He prefers to use maple, persimmon and mulberry, but also incorporates European wood such as French maple. He then skillfully combines these different materials, leveraging the grains, colors and textures of each wood. A small chest of drawers, for example, is adorned with intricate metal fittings over the joints. These subtle details add originality to Suda’s work, as he fabricates these fittings himself as well as completing all the decorative effects, such as the damascening and urushi-coating.

Gin-kan (Milky Way) conjures up stardust in the night sky, expressed by the mother of pearl inlaid on assertive grains of aniseed tree. The maxim by which Suda pursues woodworking is “purity and grace,” which extends to an unadulterated and graceful way of life as a fundamental value. Intrinsically, his life itself is manifest as creativity in his work.

Box of tamo wood (Japanese ash) with inlay, finished in wiped urushi lacquer “Ginkan” (Milky Way) 2009Kenji SUDA

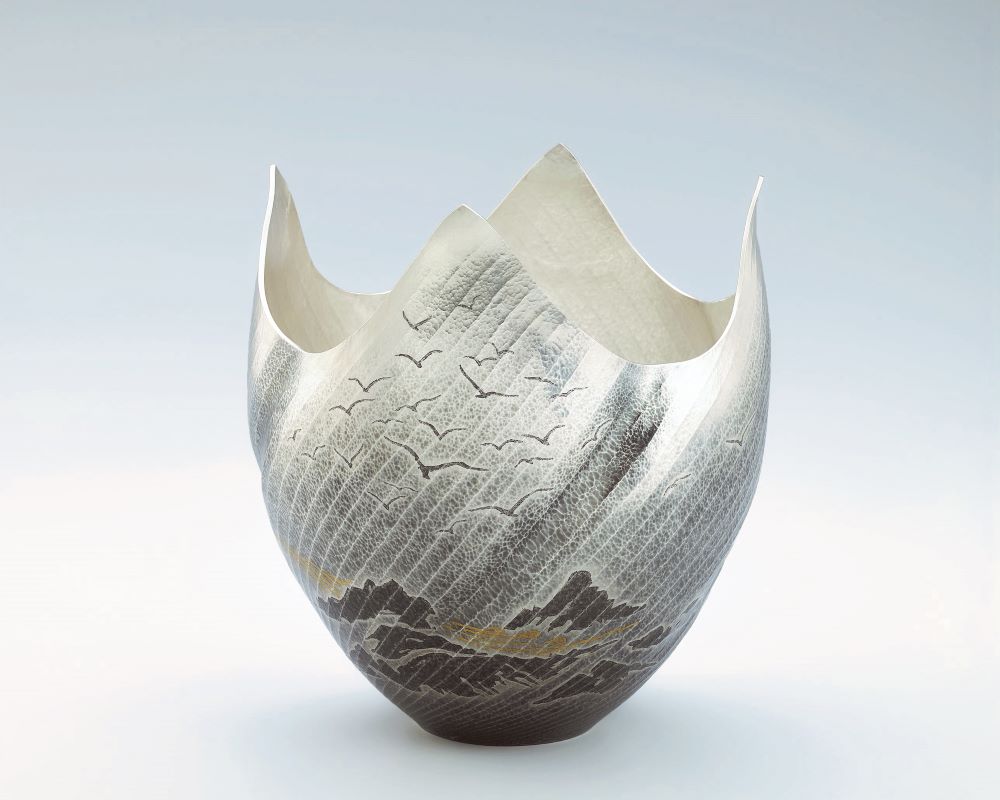

大角幸枝 | ŌSUMI Yukie

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of metal forging, designated in 2015

Yukie Ōsumi was born in 1945 in Shizuoka. After completing her studies in the arts at Tokyo University of the Arts, she undertook an apprenticeship with Shirō Sekiya (a Living National Treasure) to acquire tankin, a metal forging technique. She then learned chōkin, a metal carving technique, from Ikkoku Kashima (a Living National Treasure) and Moriyuki Katsura.

Techniques and Works

Tankin involves forging heated sheet metal with a hammer or mallet and stretching or shrinking it to create the desired form. She works predominantly with silver, which is forged into various shapes and textured with hammers, then chiseled on the surface according to her design. The grooves created are filled with pieces of gold or zinc, a technique called mesh inlay, to complete the piece of work.

Ōsumi says, “Beauty in nature is never static, and I try to capture it in the soft sheen of metal.” Metal is an attractive material for her to work on as it “has robustness and durability incomparable with other materials. It stands on the opposite end to fragility and makes a perfect medium with which to transform something in flux into a stable existence for eternity. The beauty is in that metalwork can immortalize what is essentially a mortal life.”

Forged silver flower vessel “Rough Shore” 2020Yukie ŌSUMI

森口邦彦 | MORIGUCHI Kunihiko

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of Yūzen textile, designated in 2007

Kunihiko Moriguchi, born in 1941 in Kyoto, completed his studies at Kyoto City University of Arts in 1963. He then went on to study graphic design at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in France on a French government scholarship. He aspired to establish himself as a designer in Paris until his friend Balthus pointed out to him that he should appreciate and protect his heritage, which perpetuated wonderful Japanese textiles. After returning to Japan, Moriguchi joined his father and acquired skills in traditional yūzen-style dyeing.

Techniques and Works

The resist dyeing method Yūzen was initially established in Kyoto during the seventeenth century. It is characterized by freehand lines and vibrant colors.

Snow Dance presents a black-and-white geometric pattern of snowflakes. Moriguchi meticulously executes traditional yūzen techniques to produce nature-inspired geometric designs with a modern touch. His approach to design is “to incorporate artistic elements into garments, and I aspire to stay ahead of the times.” His philosophy is that kimonos must be as functional as they are beautiful. Moriguchi says, “The arts are a celebration of being alive. They allow us to communicate beyond time and space, where we share and exchange artistic gratification.”

Yūzen kimono “Snow Dance” 2016Kunihiko MORIGUCHI

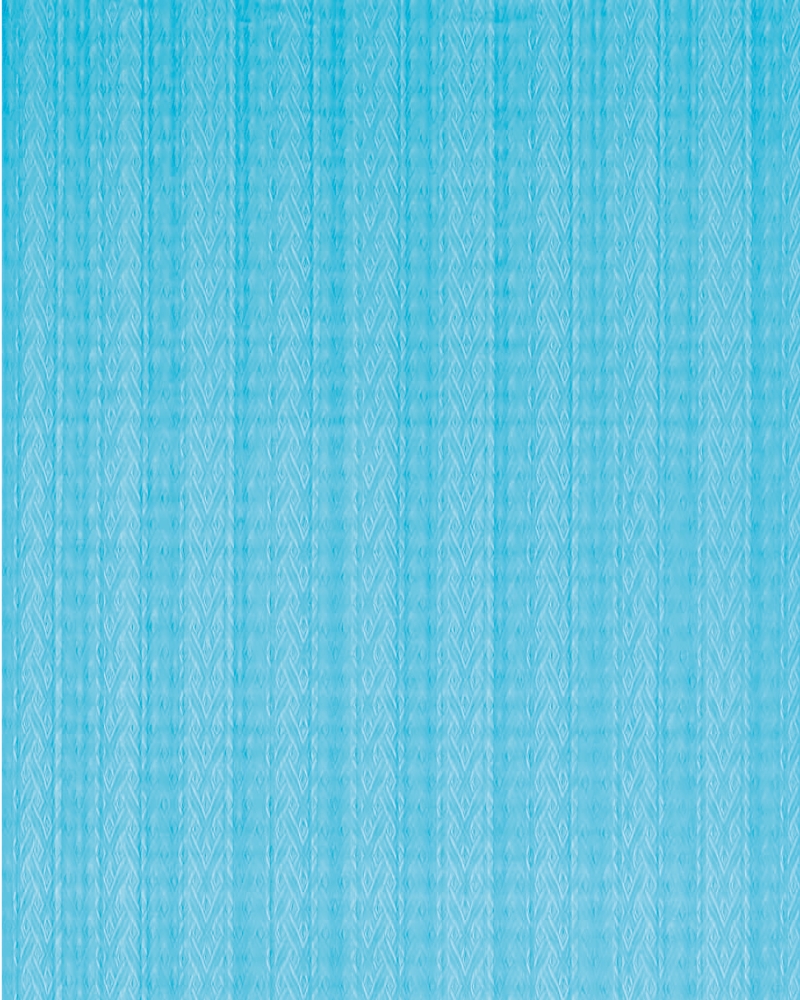

北村武資 | KITAMURA Takeshi

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the categories of ra fabric, designated in 1995, and tate-nishiki weaving, designated in 2000

Takeshi Kitamura was born in 1935 in Kyoto. He began working in the textile industry of the Kyoto district of Nishijin as a young man and became fascinated by the weaving structures of fabrics. He studied and researched various weaving techniques and attempted to revive some antiquated textiles, the ra and tate-nishiki in particular.

Techniques and Works

Once a widely-diffused material in ancient times, the ra fabric subsequently became extinct due to the complexity in production, giving way to other types of textiles in the Middle Ages. Efforts were made to recreate and preserve those ancient weaving techniques in the modern era. There are plain and patterned ra fabrics, semi-transparent depending on the density of the main weave structure, and the pattern is determined by the warps. Some ra fabrics incorporate the linen weave, but this is rare. Kitamura produces transparent patterned ra (tōmon-ra) and gold-threaded ra (ra-kin). The former is his creation, in which the pattern is depicted using the coarse-grid structure against a background in fine-grid weaving.

Mountain Stream ra gauze with see-through pattern takes inspiration from a waterfall, rendered in different shades of blue using the tōmon-ra technique. “Skills are developed through the use of the technique, giving rise to new techniques, from which new arrangements can be created.” Kitamura always retains a pioneering spirit, aspiring to create unique textiles that are relevant to modern times. His contemporary works are the result of highly technical, traditional weaving that he has mastered, and are imbued with historical and artistic significance. Sadly, he passed away in 2022.

Ra gauze with seethrough pattern “Mountain Stream” 2015Takeshi KITAMURA

佐々木苑子 | SASAKI Sonoko

Preserver of important intangible cultural properties of Japan in the category of tsumugi textiles, designated in 2005

Sonoko Sasaki, born in 1939 in Tokyo, began her apprenticeship in an atelier in Tottori and Shimane, where she learned yoko-gasuri (weft-ikat) weaving. In 1969, she opened her own atelier in Tokyo, where she continued developing her techniques and expressions through pongee and ikat textiles. She also traveled extensively in Asia to learn about other styles of textiles.

Techniques and Works

Tsumugi is woven using hand-spun silk, and the fabric has a sturdy yet soft texture to touch. The rather simple yarn fabrication, dyeing and designs give tsumugi textile a somewhat rustic feel. Sasaki is driven to produce tsumugi that is expressive through rustic textures and plant-derived natural dyes. She has established an elaborate weaving technique which enables her to incorporate ikat-style designs, creating rich effects. Patterned ikat, known as e-gasuri, is based on complex and precise planning as the warp and weft are dyed separately to achieve the intended design. Sasaki has brought tsumugi to a new level of value and creativity through her work that achieves both abstract patterns and figurative designs by leveraging the ikat-weaving method in producing tsumugi fabrics.

Green Shadow kimono of tsumugi fabric with patterned kasuri depicts an image of some water birds enjoying themselves in a pond nestled deep in the green mountain. Sasaki often incorporates birds in her designs as they represent the idea of freedom, fleeing from mundane restraints. She also aspires to create e-gasuri art that reflects her inner qualities.

Kimono of tsumugi fabric with patterned kasuri “Green shadow” 2018Sonoko SASAKI

INFORMATION

| Event title: | HOMO FABER, 12 Stone Garden Naoto Fukasawa and 12 Living National Treasures |

| From Fri. October 28 to Sun. December 11, 2022 | |

| Address & Access: | 26-2 Momoyama cho, Atami shi, Shizuoka, Japan Bus services available from Atami railway station. Take the bus bound for MOA Museum of Art from Rank 8 in the bus terminal and alight at the final stop. It takes approximately 7 minutes. |

| Organizers: | MOA Museum of Art, MICHELANGELO FOUNDATION, Japan Kōgei Association |

| With the Support of: | The Yomiuri Shimbun |

About HOMO FABER (visit HOMO FABER official website)