Exhibitions

Continuum of Rinpa Design

2025.10.24(Fri) - 2025.12.14(Sun)

Overview

These artists were not confined in a single art form. They applied their innovative designs not only to paintings, but also kōgei items such as writing boxes, kimonos, hand fans, portable containers and earthenware.

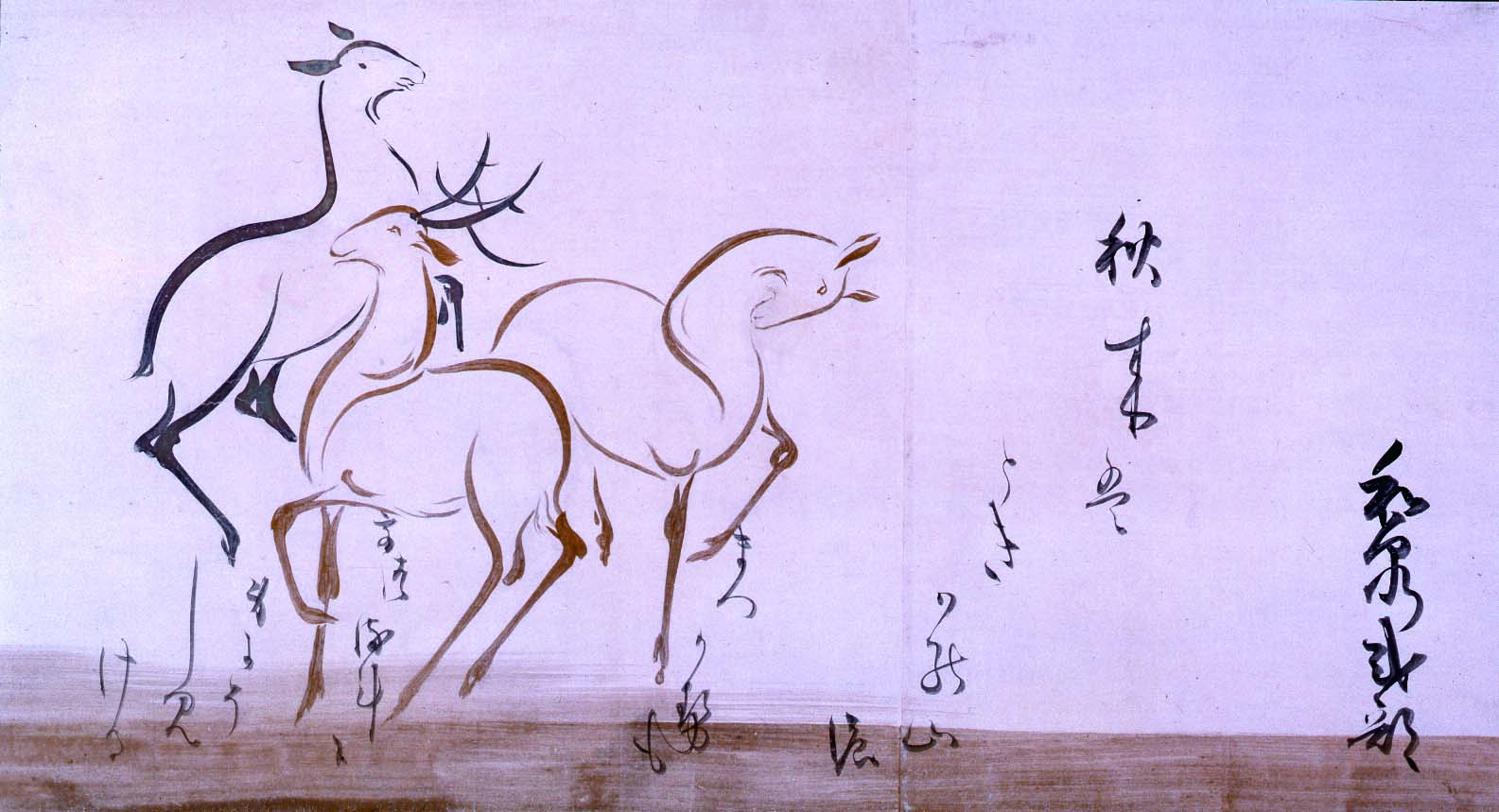

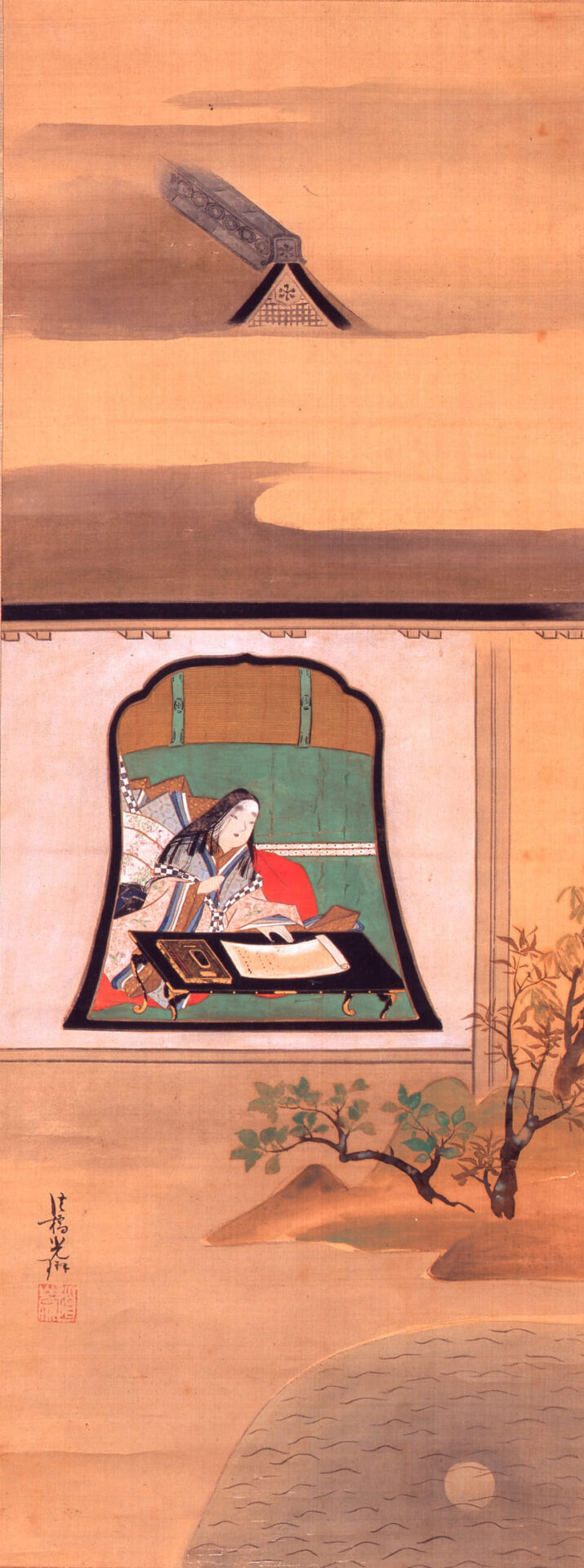

This exhibition showcases masterpieces of these prominent Rinpa artists, notably Hon’ami Kōetsu and Tawaraya Sōtatsu (Calligraphy of Poems from the ‘Shin-Kokin Wakashu’ on Paper decorated with Deer), Ogata Kōrin (The Empress Akikonomu) and Sakai Hōitsu (Snow, Moon and Flowers). Rediscover the finesse of Rinpa art the charm of which has never been lost through the passage of time.

Highlights

1. Rinpa on flora and fauna

Pickups

Calligraphy of Poems from the ‘Shin-Kokin Wakashu’ on Paper decorated with Deer, Tawaraya Sōtatsu and Hon’ami Kōetsu

Gamefowl, Tawaraya Sōtatsu

Kosode robe with design of autumn grasses, attributed to Ogata Kōrin

Covered box with design of plum blossoms, Ogata Kenzan

Snow, Moon and Flowers (Important Art Object), Sakai Hōitsu

Wisteria, Lotus and Maple, Sakai Hōitsu

2. Classical literature revisited

Pickups

Story about Nishi-no-tai, a scene from the Tales of Ise, Tawaraya Sōtatsu

The Empress Akikonomu, Ogata Kōrin

Lady Murasaki (Important Art Object), Ogata Kōrin

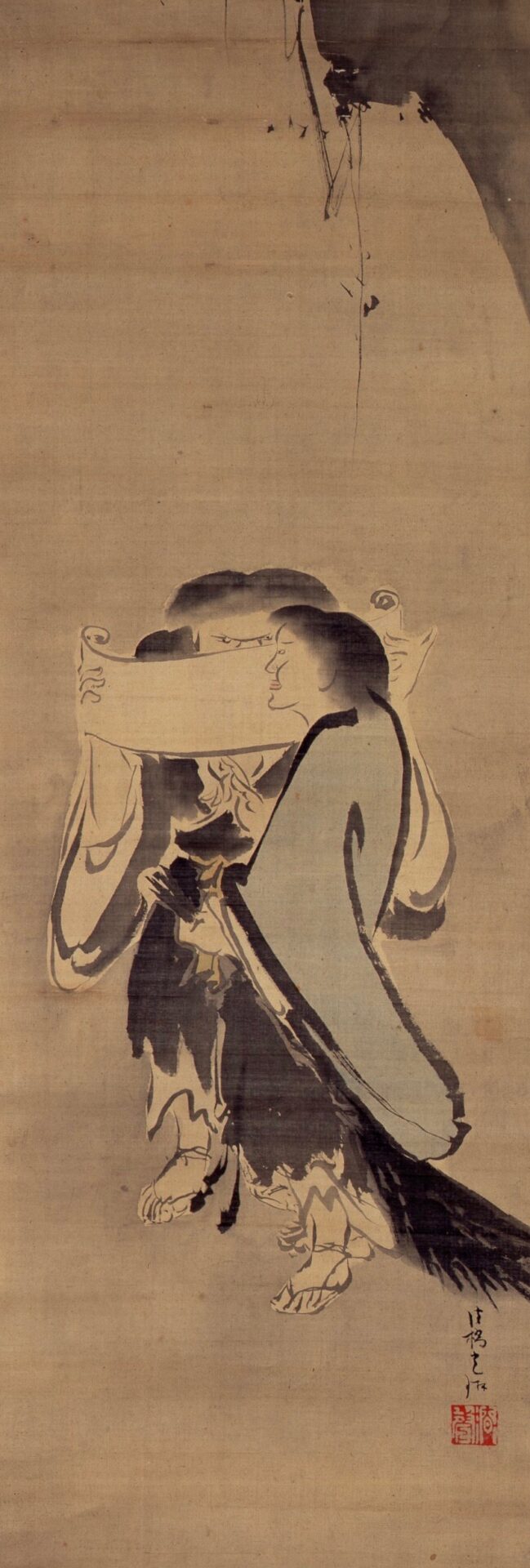

3. Themes on Buddhism

Pickups

Hanshan and Shide, Ogata Kōrin

The Immortal Qin Qao, Ogata Kōrin

Shasui Kannon, Sakai Hōitsu

■Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637)

The Hon’ami family was traditionally in the trade of sword valuation and sharpening. Kōetsu became an artist of many talents, excelling in handcrafting, calligraphy, and other pursuits. His legacies are found in many aspects of Japanese culture even today. He is also recognized as one of the three calligraphers of excellence during the period of Kan’ei (early 17th century), founding the Kōetsu-style calligraphy.

■Tawaraya Sōtatsu (birth and death unknown)

It is believed that Sōtatsu operated an art workshop and gallery named “Tawaraya.” He introduced and developed new themes in the genre of yamato-e painting, which later became the reference point of the Rinpa art style. He also developed a style to use the mogu (drawing without using outlines) and tarashikomi (smudging ink) techniques.

■Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716)

Born as the second son of a Kyoto-based kimono textile merchant, Ogata Sōken, Kōrin was introduced to many cultural pursuits during his youth as his affluent familial background permitted, such as the Noh theater, calligraphy, and painting. He was also trained in the Kanō School painting. Being familiar with the work by Kōetsu and Sōtatsu from early on, he aspired to restore his forerunners’ past glory.

His genius in design was also evident in kōgei (artisanal craft), ranging from earthenware to kimono and makie (lacquerware).

■Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743)

A younger brother of Ogata Kōrin, Kenzan was trained in pottery under Nonomura Ninsei, a Kyoto ware potter. In 1699, he opened his own kiln in Narutaki-izumitani in Kyoto and assumed a pseudonym of Kenzan. Thus, Kenzan was both his artist handle and the name of his kiln. In 1712, he relocated to a more central area, where his kiln became the household name of Kenzan ware. Much of his work reflects Rinpa-style designs, sometimes incorporating poems. He also collaborated with his brother Kōrin on many occasions.

■Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1829)

Sakai Hōitsu was born in Edo as a second son of Sakai Tadamochi, a daimyo lord of Himeji. His elder brother, Tadazane, was a man of many talents and left significant impact on Hōitsu during his formative years, notably in Japanese verses as well as art and entertainment. In terms of painting, Hōitsu started with the Kanō School and moved on to ukiyo-e style, acquiring skills and tastes of many different schools. He fostered interest in the Rinpa style during his 30s and later excelled in drawing floral designs.

Bandō Tamasaburō’s stage costumes

Friday, October 24 to Sunday, December 14

Galleries 4 and 5